Protecting Against Bioterrorism

- By : Ruben Matthews

- Category : Practices and Methods

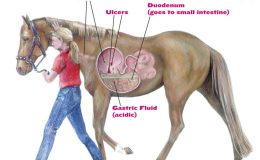

Image from VCA Animal Hospitals

Veterinarians are already versed in the understanding of infectious disease and toxicants; this understanding must now be applied to bioterrorism agents. Since the Pandora’s box of anthrax has already been opened, this discussion will be restricted to the most probable spectrum of biologic agents terrorists might consider.

Potential Agents

Bacterial agents include diseases such as anthrax, brucellosis, bubonic plague, tularemia, cholera, glanders and Q-fever. Viral agents include smallpox, Venezuelan encephalitis and viral hemorrhagic fevers caused by hantaviruses and Ebola virus. Biological toxins derived from bacteria, fungi or plants include botulinum, Staphlococcal enterotoxin B, T-2 mycotoxin (yellow rain) and ricin (castor bean).

Veterinarians will quickly note many of these also cause diseases in animals. Food animals may be specifically targeted with such viral agents such as fott-and-mouth disease virus, African swine fever virus, rinderpest virus, viral encephalidities (VEE, EEE, etc.) and exotic Newcastle disease virus. Food crops may be specifically attacked by plant disease agents such as rice blast, rye stem blast and wheat stem rust.

Forms of the Disease

Livestock, deer and other wild ruminants usually become infected by ingesting spores while grazing, or in contaminated feed (e.g. domestic and feral swine). The incubation period is three to seven days and can be peracute, acute or chronic.

In the peracute form, an animal that was normal just a few hours earlier may be found dead. Cattle, sheep, goats and deer typically have the peracute form.

Animals with the acute form may rapidly develop fever (up to 107.6 degrees Fahrenheit), stagger, tremble, and have signs of abdominal pain and respiratory distress. They may have blood-tinged diarrhea, blood in the urine and milk, and hemorrhaging from the mouth and nose. Pregnant animals may abort. Animals may die within 24 hours, with convulsions in the terminal stage of the disease. The acute form is more common in cattle, sheep, horses and deer.

Swine are typically affected with the chronic form, which produces swelling of the head and neck that often interferes with breathing and swallowing; swine may die from asphyxiation. There may be blood-tinged mucous discharge from the mouth and nose. The chronic form is also seen in horses and dogs.

Cats and dogs may develop anthrax from ingesting contaminated meat but both species seem to be resistant to inhalation anthrax. Isolation, decontamination and medication of cats and dogs exposed to anthrax spores would be an important issue in a bioterrorist event.

Anthrax can resemble other conditions that cause sudden death. In cattle and sheep, this includes clostridial infections, bloat, lightning strike, acute leptospirosis, bacillary hemoglobinuria, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and acute poisoning with bracken fern, sweet clover, lead or blue-green algae. In horses, acute equine infectious anemia, colic, lightning strike, lead poisoning and blue-green algae poisoning may resemble anthrax. In swine, classical swine fever (hog cholera), African swine fever and pharyngeal malignant edema symptoms are similar to anthrax. Poisoning and nonfatal vehicle collision could mimic anthrax in deer.

Containment and Treatment

The carcass of an animal killed by anthrax usually shows little or no rigor mortis, and there is usually dark blood oozing from the mouth, nose and anus (the blood does not clot). The body will be bloated and decompose rapidly. Do not necropsy or even cut into suspicious carcasses. A blood sample from a large vein collected through the unopened skin may be submitted for laboratory confirmation.

Animals with naturally occurring cases respond better if treated early in the course of the disease. The recommended twice daily dose of penicillin IM for livestock is 22,000 units/kg (10,000 units/pound) for five days. The daily oxytetracycline dose is five mg/kg (2.3 mg/lb) for all species. It may be given as an IM or by IV injection (slowly) in divided doses for at least 5 days. An alternative antibiotic such as ciprofloxacin may have to be used if antibiotic resistant anthrax is used in a terrorist attack. Extra-label usage of penicillin as indicated above or ciprofloxacin would require an extended withdrawal time of at least 30 days.

In anthrax outbreak situations, livestock deaths should start to subside starting at about 10 days after vaccination; a second dose of vaccine should be given two to four weeks later. Areas subjugated to terrorist attack and seeding of the ground with anthrax spores may be endemic for anthrax for a long time (depending on soil type and seasonal environmental conditions). Vaccine then will need to be administered to livestock in these geographic locations at least once yearly four weeks prior to the start of ideal environmental conditions for seasonal anthrax outbreaks. These are the same recommendations for areas of the U.S. currently having seasonal endemic anthrax outbreaks (e.g. south Texas).

Note that anthrax vaccine reactions may include: swelling at the injection site and fever for several days, hypogalactia and abortion. Milk from dairy cows developing fever post-vaccination should be destroyed. Antibiotics given within seven days of vaccine administration can make the vaccine ineffective since it is a live attenuated biologic. Animals should not go to slaughter until at least 60 days after vaccination.

One of the best ways to control any kind of anthrax outbreak is to destroy existing spores and keep from releasing more spores into the environment. Carcasses, bedding, soil and other contaminated materials should be burned as soon as possible. Burn carcasses where they lie. If carcasses must be moved, use a sled to not spread anthrax by dragging the carcass across the ground. Remember, do not open the carcass. The vegetative form of anthrax in the carcass is killed by burning. If the carcass is opened and vegetative forms are exposed to air, the transformation to the spore form will be a future source of infection. Note that thorough burning kills spores.

After a terrorist anthrax attack that kills livestock and contaminates pets, personnel in respirators and protective clothing will be needed to perform environmental clean up, pet decontamination and burning of dead animals. (Anthrax vaccination alone in clean-up workers may not provide complete protection close to the release point, so personal protective gear and respirators is a necessity.) Contaminated equipment will then have to be sanitized with a sporocidal disinfectant, such as five percent sodium hydroxide (lye). Ordinary disinfectants are not effective against the spore form of anthrax.

The disease management technique of isolating sick animals undergoing treatment from healthy-appearing animals should be practiced within the confines of that immediate premise. No animals should be moved off the premise until at least 10 days after all livestock are vaccinated and all carcasses have been properly disposed. The number of quarantine days may be extended in the special case of terrorist attack, when livestock (and many other animals, pets, etc.) may be exposed by unnatural routes of infection (eg. inhalation, cutaneous or combinations).

No Comments